Editor’s Note: Two years ago, Mayor Miro Weinberger announced that Burlington was one of several communities around the country chosen to be part of an effort called U.S. Ignite. This national nonprofit links cities that have gigabit-speed fiber-optic networks, giving them the tools to collaborate and share resources related to their valuable telecommunications infrastructure.

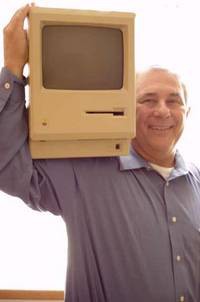

On October 29, 2015, the local effort, christened BTV Ignite, hosted a roundtable discussion featuring city officials and business leaders, as well as representatives from other U.S. Ignite cities, including Cleveland, Ohio; Kansas City, Mo.; and Chattanooga, Tenn. Burlington product designer Jerry Manock, who helped design the original Macintosh computer, was one of about 100 people who attended. He wrote an open letter to BTV Ignite, which we’ve published here, below.

Technology as a Tool

By: Jerry Manock, Principal Member, Manock Comprehensive Design L.L.C., Burlington, Vermont

As a principal of a product design consulting firm for 39 years, and as a former Corporate Manager of Product Design at Apple Computer for five years, I feel qualified to comment on BTV Ignite’s mission and charter as a champion of high-tech innovation in Burlington and, in particular, on the October 29 roundtable.

Let me say up front that the afternoon discussion of Burlington Telecom’s potential as a national leader in bringing ultra-high-speed Internet to our area was very impressive. The fact that Burlington, population 42,000, was chosen to be a member of the U.S. Ignite program along with much larger cities speaks volumes about the foresight of those who developed Burlington Telecom’s fiber-optic network in 2003.

Likewise, the recent selection of former Burlington police chief Michael Schirling as BTV Ignite’s Executive Director immediately brings a solid foundation of energy and expertise to the program.

I do, though, have comments on the content and focus of what was presented.

Mayor Weinberger described his vision of Burlington being known as a “great tech city.” He stated that he wants to “leverage BT’s fiber optics resources” toward “accelerating the tech economy.”

Michael Schirling described his encouraging goal of involving K-12 educational initiatives and college involvement in his vision of BTV Ignite’s charter.

Yaw Obeng, Burlington’s new Superintendent of Schools, then spoke of the value of BTV Ignite to the “4,000 future workers” who are students in our public schools, and of a 21st Century education filling the “gaps and needs of our business community.”

This is where a tiny voice in my head started its questioning. Why did Dr. Obeng refer to our students as “future workers” instead of “future citizens?” And is the goal of our public educational system broader than servicing employers’ needs?

Representatives from other Ignite cities seemed to offer a more expansive vision. Lev Gonick, Chief Executive Officer of OneCommunity, in Cleveland spoke about its Ignite program and how a major goal was to help alleviate poverty in their city. I resonated with this much broader, more humanistic goal.

Ken Hays, President and CEO of The Enterprise Center, in Chattanooga spoke of its city-owned fiber optic network and how it was an early 1 gigabit city, soon to be a 10 gigabit city. He highlighted the new opportunities in medical practice applications that such a large bandwidth would allow. That’s certainly directly applicable to our local medical institutions.

The highlight for me, though, were the comments from Aaron Deacon, Executive Director of KC Digital Drive, in Kansas City. He related that his city’s chosen Ignite program concentrated on increasing “the social impact of their tech assets,” giving it a civic focus on improving residents’ quality of life, which is similar to Smart City initiatives worldwide.

Why did I consider this a highlight? U.S. Ignite and BTV Ignite both have a three-pronged mission: “Economy, Education, and Community.” On the BTV Ignite website the lead sentence under Community reads “U.S. Ignite is focused on developing next generation applications that have transformative public benefit” (my underlined emphasis).

Although my entire career has been involved with technological advances, I increasingly value consideration of what social impact advancing technology will have.

Robert McKim, my product design professor at Stanford University, thought us to run every idea through a “profundity filter.” He reasoned that vast amounts of mental and physical energy would be expended by individuals in developing a new product. He wanted us to make a conscious decision about whether this energy expenditure would do some good in the world — whether it would improve people’s lives.

Over and above potential financial compensation or the “coolness” of the tech involved, he wanted the profundity factor to be included when deciding whether or not to work on a project. I sincerely hope that this criteria will be part of the BTV Ignite playbook as it has been in Cleveland and Kansas City.

How do we introduce the profundity filter? I believe the answer lies in the education of our students. Along with teaching the latest high-tech STEM topics, a K-12 curriculum needs to include courses in the humanities — history, ethics, social studies, etc. Students must be aware of cultural topics in order to be able to design products and services that satisfy the needs of each segment of our society.

And students need to work on real-world problems, not simply theoretical academic exercises. This can be done with the help of community business and government volunteers who are willing to present problems, answer questions along the way, and then review the solutions the students propose.

A model for this experiential education can be found in the Feasibility Study for the proposed Technical/Academic High School that was presented to Chittenden County voters 10 or so years ago. The concepts in that study were taken from best practices of existing schools in every part of the U.S. and remain vitally relevant today. An example is the “Zoo School” outside of Minneapolis. In schools like this the students know why they are learning subjects because with these “tools” they are contributing to solving problems that are valued by their community, their state, their country, and the world. Their reward is making a relevant global

contribution.

So, through programs like BTV Ignite, our students can be encouraged to learn how to program applications (apps) for computers and mobile devices. With these skills, and the amazing fiber-optic network Burlington already has, they will then have to decide what to work on. They can choose to create lifelike combat video games, work on CGI for highly realistic superhero movies, or 3-D print intricate party favors.

Alternatively, by adding a profundity filter to their education, many will choose to apply their seemingly unbounded energies to solving meaningful, real problems.

My hope is that during its formative period, BTV Ignite will follow the example of the Cleveland and Kansas City Ignite programs, and will realize that high technology is a tool to create a better world, not an end in itself.